Was there a revelation for Barto already? Unknown facts about famous writers. Agnia Barto Read in the summer Agnia Barto Samuil Marshak

There is an expression "a turning point" - there was a "turning point" in my life. I have preserved material evidence of it: a self-made album, covered with verses from cover to cover. Reading them, it is difficult to imagine that they were written after the revolution, in its first tense years. Next to the mischievous epigrams about teachers and girlfriends, numerous gray-eyed kings and princes (a helpless imitation of Akhmatova), knights, young pages who rhymed with "madam" felt calm and firmly in my poems ... But if you turn this album over, so to speak, "back to front", then the entire royal army will disappear as if by a wave of a wand.

On the reverse side of the album sheets there is a completely different content, and instead of neat quatrains, the lines go in a ladder. This metamorphosis took place in one evening: someone forgot in our hallway, on the table, a small book of poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky.

I read them in one gulp, all in a row, and then, grabbing a pencil, on the back of a poem dedicated to the teacher of rhythm, which began with words:

Were you once

Pink marquise... -

wrote to Vladimir Mayakovsky:

be born

New person,

So that the rot of the earth

Extinct!

I hit you with my forehead

century,

For what I gave

Vladimir.

The lines, of course, were weak, naive, but, probably, I could not help but write them.

The novelty of Mayakovsky's poetry, the rhythmic boldness, the amazing rhymes shocked and captivated me. From that evening, the ladder of my height went up. She was quite steep and uneven for me.

I first saw Mayakovsky alive much later. We lived in a dacha in Pushkino, from there I went to Akulova Gora to play tennis. That summer I was tormented from morning to evening by words, twirled them in every way, and only tennis knocked rhymes out of my head. And then one day, during the game, getting ready to serve the ball, I froze with a raised racket: behind the long fence of the nearest dacha I saw Mayakovsky. I recognized him immediately from the photo. It turned out that he lives here. It was the same dacha where the sun came to visit the poet ("An extraordinary adventure that happened with Vladimir Mayakovsky in the summer at the dacha", "Pushkino, Akulova Gora, Rumyantsev's dacha, 27 miles along the Yaroslavl Railway."). Then I watched more than once from the tennis court how he walked along the fence, thinking about something. Neither the voice of the referee, nor the cries of the players, nor the sound of balls interfered with him. Who would have known how I wanted to approach him! I even thought of what I would say to him: “You know, Vladimir Vladimirovich, when my mother was a schoolgirl, she always learned her lessons, walking around the room, and her father joked that when he gets rich, he will buy her a horse so that she is not so tired” . And here I will say the main thing: "You, Vladimir Vladimirovich, do not need any crow's horses, you have the wings of poetry." Of course, I did not dare to approach Mayakovsky's dacha and, fortunately, did not utter this terrible tirade.

A few years later, the editor of my books, the poet Natan Vengrov, asked me to show him all my poems, not only for children, but also for adults, written "for myself." After reading them, Vengrov felt my ardent, but student enthusiasm for "Mayakov's" rhythms and rhymes, and said just the words that I should have said then: "Are you trying to follow Mayakovsky? But you follow only his individual poetic methods ... Then make up your mind - try to take a big topic."

This is how my book "Brothers" was born. The theme of the brotherhood of the working people of all countries and their children, new to the poetry of those years, captivated me. Alas, the bold decision of a significant topic turned out to be beyond my power. There were many imperfections in the book, but its success with children showed me that it was possible to talk with them not only about small things, and this made me addicted to a big topic. I remember that in Moscow, for the first time, a children's book holiday was organized - "Book Day". Children from different districts walked around the city with posters depicting the covers of children's books. The children moved to Sokolniki, where they met with the writers. Many poets were invited to the celebration, but only Mayakovsky came from the "adults". The writer Nina Sakonskaya and I were lucky: we got into the same car with Vladimir Vladimirovich. At first they drove in silence, he seemed focused on something of his own. While I was thinking about how to start a conversation smarter, the quiet, usually silent Sakonskaya spoke to Mayakovsky, to my envy. I, being by no means a timid ten, became shy and did not open my mouth all the way. And it was especially important for me to talk with Mayakovsky, because doubts seized me: isn't it time for me to start writing for adults? Will I get anything?

Seeing in Sokolniki Park, on the site in front of the open track, a buzzing, impatient crowd of children, Meyakovsky was excited, as they are excited before the most important performance. When he began to read his poems to the children, I stood behind the stage on the ladder, and I could see only his back and the waves of his arms. But I saw the enthusiastic faces of the guys, I saw how they rejoiced at the very verses, and the thunderous voice, and the gift of oratory, and the whole appearance of Mayakovsky. The guys clapped so long and loudly that they scared away all the birds in the park. After the performance, Mayakovsky, inspired, descended from the stage, wiping his forehead with a large handkerchief.

Here is the audience! They need to write for them! he said to the three young poetesses. One of them was me. His words meant a lot to me.

Soon I knew that Mayakovsky was writing new poems for children. He wrote, as you know, only fourteen poems, but they are rightfully included in "all one hundred volumes" of his party books. In poems for children, he remained true to himself, did not change either his poetics or the variety of genres characteristic of him. I tried to follow the principles of Mayakovsky (albeit studently) in my work. It was important for me to assert for myself the right to a big topic, to a variety of genres (including satire for children). I tried to do it in a form that is organic for myself and accessible to children. Nevertheless, not only in the first years of my work, I was told that my poems are more about children than for children: the form of expression is complex. But I believed in our children, in their lively mind, in the fact that a small reader would understand a big idea.

Much later, I came to the editorial office of Pionerskaya Pravda, to the department of letters, hoping that in children's letters I could catch the children's lively intonations, their interests. I was not mistaken and told the editor of the department:

You were not the first to come up with this, - the editor smiled, - back in 1930, Vladimir Mayakovsky came to us to read children's letters.

Many people taught me to write poetry for children, each in his own way. Here Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky listens to my new poem, smiles, nods his head benevolently, praises the rhymes. I blossom from his praise, but he immediately adds, not without malice:

It would be very interesting for me to listen to your unrhymed poems.

I'm confused: why "without rhymes" if he praises my rhymes? The rhyme that came into my head sometimes gives rise to a thought, suggests the content of a future poem. I internally protest.

Korney Ivanovich again returns to unrhymed verses in his New Year's letter to me from Leningrad ("4 am, among Nekrasov's proofs"). “The whole power of such verses,” he writes, “is in the lyrical movement, in the inner passages, and this is how the poet is known. Rhymeless verses are like a naked woman. It’s easy to be beautiful in the clothes of rhymes, but try to dazzle with beauty without any ruffles, frills, bras and other aids.

Still, I do not understand Chukovsky! He contradicts himself, in his "Commandments for Children's Writers" he says: "Those words that serve as rhymes in children's poems should be the main bearers of the meaning of the whole phrase." And why should I write without rhyme?!

But still, "frills and frills" haunt me. Only gradually, with chagrin, do I realize that Chukovsky lacks in my poems "lyrical movement", that same lyricism that at the beginning of my work he spoke to me with all frankness and frankness. (In those years it was not customary to talk to young people as carefully as now.) I remember his words: “it sounds funny, but small”, “you have your own rhymes, although magnificent ones alternate with monstrous ones”, “here you have pop wit, dear my ... only lyricism makes wit humor."

No, Korney Ivanovich does not contradict himself, he wants to make me understand that rhymes, even the most brilliant ones, will not replace lyricism. It turns out that we are talking about the most important thing again, only in a more delicate form.

If Korney Ivanovich knew how many real, "lyrical" tears were shed in those days by me in poems written only for myself, where I was tormented by the fact that I lacked lyricism. It was wet from these tears in my desk drawer. Nor did Korney Ivanovich know that back in 1934 he himself called me a "talented lyricist." And he did not name it anywhere, but in the Literary Gazette. There was a long history behind this.

In May 1934, I was returning from friends to Moscow in a suburban train. In those days, news came of the rescue of the Chelyuskinites. Until recently, millions of hearts were full of great anxiety: how are they there, on an ice floe, cut off from the world?! What will happen to them if the spring sun melts the ice floe? But now all the hearts were overwhelmed with joy - saved! This was said everywhere and everywhere, even on the suburban train. And a poem was spinning in my head, or rather, only the beginning of it, a few lines from the boy's face. Suddenly, at one of the stations, Chukovsky entered the car. Communication with Korney Ivanovich has always been unusually interesting and important for me, and in those early years of my work, an accidental meeting in a carriage with Chukovsky himself seemed to me a gift from above.

"I wish they could read my lines!" I dreamed. The situation in the car was hardly suitable, but the temptation to hear what Korney Ivanovich would say was great, and as soon as he settled down on the bench next to me, I asked:

May I read you a poem... very short...

A short one is good, - said Chukovsky, - read read ... - And suddenly, with a sly wink at me, he turned to the passengers sitting nearby: - The poetess Barto wants to read her poems to us!

Some of the passengers, smiling incredulously, prepared to listen. I was confused, because Chukovsky could not leave a stone unturned from my poems, and even in front of everyone ... I began to deny:

I didn't want to read my own poetry.

But whose? asked Korney Ivanovich.

One boy, - I answered, in order to somehow get out of a difficult situation.

Poems of a boy? Especially read, - demanded Korney Ivanovich.

And I read:

Chelyuskins-Dorogins!

How I feared spring!

How I feared spring!

In vain I was afraid of spring!

Chelyuskintsy-Dorogintsy,

You are still saved...

Excellent, excellent! Chukovsky rejoiced with his usual generosity. How old is this poet?

What was I to do? It was great to mow down the age of the author.

He's five and a half, I said.

Read it again, - Korney Ivanovich asked and, repeating the lines after me, began to write them down: he wrote down the "Chelyuskinites" and one of the passengers. I was neither alive nor dead ... I did not have the courage to immediately confess my involuntary deceit, but the feeling of awkwardness remained and grew every day. At first I wanted to call Korney Ivanovich, then I changed my mind: it was better to go to him, but it turned out that he was already in Leningrad. I decided to write a letter. And suddenly, in the midst of my torments, I open Litgazeta and begin to wonder if I am having a hallucination. I see the title: "Chelyuskin-Dorogin" and the signature: "K. Chukovsky."

Here is what was written there:

“I am far from delighted with those pompous, phrase-mongering and flabby poems that I happened to read on the occasion of the rescue of the Chelyuskinites ... Meanwhile, in the USSR we have an inspired poet who dedicated an ardent and sonorous song to the same topic, gushing straight from the heart The poet is five and a half years old ... It turns out that a five-year-old child was sick of these Doroginians no less than we are ... That is why in his poems it is so loud and stubbornly repeated "How I was afraid of spring!" And with what economy of visual means he conveyed this deeply personal and at the same time all-union anxiety for his "Doroginians"! The talented lyricist boldly breaks his entire stanza in half, immediately translating it from minor to major:

In vain I was afraid of spring!

Chelyuskintsy-Dorogintsy,

Still, you are saved.

Even the structure of the stanza is so refined and so original ... "

Of course, I understood that these praises were caused by a feature of Korney Ivanovich's character: his ability to ruthlessly crush what he does not accept, and just as immensely admire what he likes. In those days, apparently, his joy was so all-encompassing that it also affected the assessment of poetry. I also understood that now I need to be silent and forget that these lines are mine. My husband's mother, Natalia Gavrilovna Shcheglyaeva, was also dismayed; every phone call thrilled her. "They will ask you, where is this boy? What is the boy's last name? What will you answer?!" she was killed. Her fears turned out to be in vain, the name of a talented child did not interest anyone. But what began, oh, what began after Chukovsky's note! In a variety of radio programs dedicated to the ice epic, as if to reproach me, "Chelyuskin-Doroginites" sounded every now and then. By the arrival of the heroes, a special poster was released: a children's drawing, signed with the same lines. The streets were filled with posters announcing a new variety show "Chelyuskintsy-Dorogintsy". My husband and I went to the concert, the lines followed me on the heels: the entertainer read them from the stage, and I had the opportunity to personally clap the "juvenile author".

Years later, when the imaginary child could well have reached adulthood, Korney Ivanovich suddenly asked me:

Do you keep recording children's words and conversations?

I continue. But I don't have anything particularly interesting.

Still, give them to me for the new edition of Two to Five. Only "for children," Korney Ivanovich emphasized and, smiling, shook his finger at me.

Chukovsky demanded from me more thoughtfulness, the severity of the verse. On one of his visits from Leningrad, he came to visit me. As usual, I'm eager to read him a new poem, but he calmly removes Zhukovsky's volume from the shelf and slowly, with obvious pleasure, reads Lenore to me.

And now, as if a light lope

The horse resounded in silence

Rushing across the field of riders!

Rattled to the porch,

He ran rattling onto the porch,

And the ring rattled on the door.

You should try to write a ballad, - says Korney Ivanovich as if in passing. The "mode of ballads" seemed alien to me, I was attracted by Mayakovsky's rhythm, I knew that Chukovsky also admired him. Why should I write a ballad? But it so happened that after some time I visited Belarus, at the border outpost; returning home, thinking about what I saw, I, unexpectedly for myself, began to write a ballad. Perhaps its rhythm was prompted to me by the very atmosphere of the forest outpost. But the first clue was, of course, Korney Ivanovich. The ballad was not easy for me, every now and then I wanted to break the meter, "disarrange" some lines, but I kept repeating to myself: "Stronger, stricter!" Chukovsky's praise was my reward. Here is what he wrote in the article “Harvest Year” (“Evening Moscow”): “It seemed to me that she would not be able to master the laconic, muscular and winged word necessary for ballad heroism. And with joyful surprise I heard her the other day in the Moscow House of Pioneers ballad "Forest outpost".

Forest outpost... squat house.

Tall pines behind a dark window...

Dreams descend into that house for a short while,

There are rifles against the wall in that house.

Here near the border, a foreign land,

Here, our forests and fields are not nearby.

"A strict, artistic, well-constructed verse, quite corresponding to a large plot. In some places, breakdowns are still noticed (which the author can easily eliminate), but basically it is a victory ..."

Having made a severe diagnosis of my early poems: “there is not enough lyricism,” Korney Ivanovich himself suggested poetic means to me, which helped me to breathe. But the thought did not leave me that after all this was not my main path, I should strive for greater lyricism in cheerful, organic poems for me.

Thanks to Korney Ivanovich and for the fact that he treated my early rhymes with sincere attention, among which there were indeed "monstrous" ones. In one of my first children's books, Pioneers, I managed to rhyme:

The boy is standing by the linden,

Cries and sobs.

They told me: what kind of rhyme is this “standing” and “sobbing”. But I strongly argued that it should be read like this. She proved, despite the fact that a parody appeared on these lines:

The train is moving

The head of the station sells cottage cheese.

Chukovsky was amused by my "sobbing," but he encouraged the attraction to playful, complex rhyme, the desire to play with words. And when I succeeded in something, he rejoiced at the discovery, repeated a complex or punning rhyme several times, but believed that the rhyme in a nursery rhyme must be accurate, did not like assonances. I could not agree with him in any way, it seemed to me that "free" assonance rhymes are also quite appropriate in poetics for children. I did not dare to challenge the opinion of Korney Ivanovich, but I needed convincing arguments in defense of "free" rhyme, I did not want to, I could not deviate from my understanding of the possibilities of children's verse. And I found these arguments for myself - although I wrote and now I write intuitively. Here they are: an adult, listening to poetry, mentally sees how the word is written, for him it is not only audible, but also visible, and little ones cannot read, only rhyme "for the eye" is not necessary for them. But "free rhyme" can in no way be arbitrary; the deviation from the exact rhyme must be compensated by the fullness of the sound of the rhyming lines. Sound rhyming attracted me also because it gives room for new bold combinations. How tempting to open them! For confirmation of my arguments, I turned to folk poetry, my passion for it then began. It is curious that many years later, in 1971, V. A. Razova, while working on her doctoral dissertation "The Folklore Origins of Soviet Poetry", wrote to me: "I ask myself questions that only you can answer ... the fact is, that many of your poems have been recorded by folklorists in collections of folk songs, sayings... Where did you get this feeling of folk, meadow, peasant? was it the result of painstaking research, acquaintance with folklore collections?

Yes, I had a nanny, Natalia Borisovna, who told me fairy tales, but I did not answer the question about the nanny, so that, God forbid, I would not evoke associations with Arina Rodionovna and thereby put myself in a ridiculous position. Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky - that's who infected me with his love for oral folk art. He spoke with such admiration and conviction about the wisdom and beauty of folk poetic speech that I could not help but be imbued with his faith: outside this fertile soil, Soviet children's poetry cannot develop. And how delighted I was when I first found this proverb:

A crow flew in

In high mansions.

My first research in the field of rhyme convinced me that sayings, songs, proverbs, along with exact rhymes, are also rich in assonances.

With the fear of God, I read to Korney Ivanovich one of my first satirical poems, Our Neighbor Ivan Petrovich. At that time, pedagogical criticism resolutely rejected this genre: "Satire? For children?" And then there's satire on an adult! I read to Chukovsky with another anxiety - what if he says again: "Wit"? But he happily said: "Satire! That's how you should write!"

Is the humor real? Will it reach the children? I asked.

To my joy, Chukovsky supported my "children's satire" and always supported. Let them not reproach me for immodesty, but I will quote excerpts from his two letters so as not to be unfounded.

... "Grandfather's granddaughter" (a book of satire for schoolchildren. A. B.) I read aloud and more than once. This is a genuine "Shchedrin for Children" ... "Younger Brother" is a smiling, poetic, sweet book ...

Your Chukovsky (senior)".

"February 1956 Peredelkino.

Your satires are written on behalf of children, and you talk to your Yegors, Katyas, Lyubochkas not as a teacher and moralist, but as a comrade wounded by their bad behavior. You artistically reincarnate in them and reproduce their voices, their intonations, gestures, the very manner of thinking so vividly that they all feel you are their classmate. And, of course, not you, but shorn first-graders-boys make fun of touchy and sneak:

Touch her by accident

Immediately - guard!

Olga Nikolaevna,

He pushed me...

All your Korney Chukovsky.

My concern: "Will it reach the children?" - Korney Ivanovich understood like no one else. I once read Vovka, my little nephew, "Moydodyr". From the first line "The blanket ran away, the sheet jumped" and to the last "Eternal glory to the water" he listened without moving, but he made his own conclusion, completely unexpected: "Now I will not wash!" - "why?" - I was in a hurry. It turned out: Vovka is eager to see how the blanket will run away and the pillow will jump. The picture is tempting!

On the phone, laughing, I told Korney Ivanovich about this, but he did not laugh. Angrily exclaimed:

You have a strange nephew! Bring him to me! The illustrious author of "Moydodyr", beloved by children, was sincerely alarmed because of a few words of the four-year-old Vovka!

My insomnia reminded me of Tashkent ... It's better to read funny poems to me, - asked Korney Ivanovich.

I didn’t have new funny poems, I read a poem I had just written about a lonely puppy "He was all alone."

Looking at me carefully, Chukovsky asked:

Has something happened to you... Or to your loved ones?

It really happened: I was in great anxiety about the illness of a person close to me. But how could Korney Ivanovich feel this personal, spiritual confusion in poems written for children, and even with a good ending?

Then you added the end, - said Chukovsky.

On the book that was presented to me that day (Volume 5 of the Collected Works), he made the following inscription: "To my dear friend, beloved poet Agniya Lvovna Earto, in memory of June 14, 69."

After June 14, we never saw each other again. But Korney Ivanovich fulfilled his promise - he sent me a clipping from a Tashkent newspaper, yellowed from time to time, and this gave me the opportunity to talk about his work in one of the radio programs. But after his death.

It is perhaps the most difficult thing for me to tell about how I studied with Marshak. Our relationship was far from easy and did not immediately develop. Circumstances were to blame in some ways, we ourselves were in some ways. Usually a schoolboy, when he writes about one of his classmates, is recommended first of all to give a picture of that time. The advice is useful not only for schoolchildren, I will try to use it.

Writers - my peers - remember, of course, what a complex, in many ways confused situation was in the literary environment of the late 1920s and early 30s. Literary organizations were then led by the All-Union Association of Associations of Proletarian Writers - VOAPP and separated from it into an independent organization RAPP (Russian Association of Proletarian Writers). It, in turn, united MAPP (Moscow Association), LAPP (Leningradskaya) and other APPs. Various literary associations were created, disintegrated and re-emerged. The early theoreticians divided the young Soviet literature into proletarian and "fellow travelers", and the "fellow travelers" themselves - additionally into "left" and "right". In one of the notebooks my satirical poem of those years has been preserved.

Call 1st

Hello, who is this?

Is that you, Barto?

How are you doing?

Do you read newspapers?

Have you read Razin's article?

He dispossesses you there.

He writes that your book "About the war" -

Ugliness

And that the opportunist is not otherwise you.

Of course you understand

What about us, your friends -

Writers

It's terribly outrageous

Terribly outrageous!

But don't be upset

Be sure to read

Until then, all the best

Farewell.

Call 2nd

Is it one thirty eight twenty?

Barto, I need to see you.

They say you are one of the best

Are you the closest left fellow traveler?!

And in general, you are now famous to hell,

Even Vechorka wrote about you.

Call 3rd

Is this Barto's apartment?

That is, like "What"?

I want to know if Barto is alive?

Or has it already been chewed up?

They say she sucked on the MAPP

I put my mom and dad there,

Now she's being chased everywhere.

Tell me when the cremation

I will gladly.

Call 4th

Comrade Barto, would you like to

In the All-Russian Union in the leaders?

Why are you so excited?

Everything will be coordinated with MAPP and VAPP.

And by the evening

My head is shining

And at night

I jump out of bed

And I scream:

go away

Get away!

Do not call,

Don't torment!

Who am I? -

Tell:

Supervisor?

opportunist?

Or a travel companion?

But the organizational confusion in the life of writers came to an end. For many, the Decree of the Central Committee of the Party of April 23, 1932 on the radical "restructuring of literary and artistic organizations" was unexpectedly heard.

Still, I have to go back to the RAPP days. Long before my comic poems were written, an article appeared in the magazine On Post, in which I was opposed to "a young, beginning writer" no more, no less than Marshak himself! And this at a time when my poems could only be judged by the manuscript (my first book had not yet been published), and Marshak was already a famous poet, the author of many smart, cheerful poems that affirmed high postural principles. Naturally, the appearance of such an article could not but arouse Marshak's internal protest. Of course, I was also aware of the flimsiness of the article, which claimed that I understood the psychology of children from the proletarian environment better than Marshak, but I did not think then that the article would bring me so many unpleasant experiences and I would long remember her with an unkind word. It was published in 1925, but its consequences continued to be felt during the five or six years of my work. Marshak reacted negatively to my first books, I would even say intolerant. And Marshak's word already had great weight then, and negative criticism mercilessly "glorified" me. On one of Samuil Yakovlevich's visits to Moscow, when he met at the publishing house, he called one of my poems weak. It really was weak, but I, stung by Marshak's irritation, could not bear it, repeated other people's words:

You may not like it, you are the right fellow traveler!

Marshak grabbed his heart.

For several years our conversations were conducted on a knife edge. He was angry with my obstinacy and some straightforwardness, which was characteristic of me in those years. For example, when I met someone I knew, I often exclaimed with complete sincerity: "What is the matter with you? You look so terrible!" - until one kind soul explained to me in a popular way that such sincerity is not needed at all: why upset a person, it is better to encourage him.

I learned this lesson too zealously: sometimes I caught myself saying even on the phone:

Hello, you look great!

Unfortunately, I behaved too straightforwardly in conversations with Marshak. Once, not agreeing with his amendments to my poems, afraid of losing her independence, she said too passionately:

There are Marshak and undermarshas. I can't become a marshak, but I don't want to be a runner!

Probably, Samuil Yakovlevich had to work hard to keep his composure. Then I asked more than once to excuse me for the "right fellow traveler" and "marshamen". Samuil Yakovlevich nodded his head: "Yes, yes, of course," but our relations did not improve.

I needed to prove to myself that I could do something. Trying to maintain my position, in search of my own path, I read and re-read Marshak.

What did I learn from him? The completeness of thought, the integrity of each, even a small poem, the careful selection of words, and most importantly, a lofty, demanding look at poetry.

Time passed, occasionally I turned to Samuil Yakovlevich with a request to listen to my new poems. Gradually he became kinder to me, so it seemed to me. But he rarely praised me, scolded me much more often: I change the rhythm unjustifiably, and the plot is not taken deep enough. Praise two or three lines, and that's it! I almost always left him upset, it seemed to me that Marshak did not believe in me. and one day with despair said:

I won't waste your time anymore. But if someday you will like not individual lines, but at least one of my poems in its entirety, I beg you, tell me about it.

We did not see each other for a long time. It was a great deprivation for me not to hear how he quietly, without pressure, reads Pushkin in his breathless voice. It is amazing how he was able to simultaneously reveal the poetic thought, and the movement of the verse, and its melody. I even missed the way Samuil Yakovlevich was angry with me, constantly puffing on a cigarette. But one morning, unforgettable for me, without warning, without a phone call, Marshak came to my house. In front, instead of greeting, he said:

- "Bullfinch" is a wonderful poem, but one word needs to be changed: "It was dry, but I dutifully put on galoshes." The word "obediently" here is someone else's.

I'll correct the word "submissively." Thank you! I exclaimed, hugging Marshak.

Not only was his praise infinitely dear to me, but also the fact that he remembered my request and even came to say the words that I so wanted to hear from him.

Our relationship did not immediately become cloudless, but the wariness disappeared. The stern Marshak turned out to be an inexhaustible inventor of the most incredible stories. Here is one of them.

Somehow in the autumn I ended up in the Uzkoye sanatorium near Moscow, where Marshak and Chukovsky were resting just in those days. They were very considerate towards each other, but they walked apart, probably did not agree on any literary assessments. I was lucky, I could walk with Marshak in the morning, and after dinner - with Chukovsky. Suddenly one day a young cleaning lady, wielding a broom in my room, asked:

Are you a writer too? Do you also work at the zoo?

Why at the zoo? - I was surprised.

It turned out that S. Ya. told a simple-hearted girl who had come to Moscow from afar that, since writers’ earnings are inconsistent, in those months when they are having a hard time, they depict animals in the zoo: Marshak puts on the skin of a tiger, and Chukovsky (“long from room 10") dresses up as a giraffe.

They are well paid, - said the girl, - one - three hundred rubles, the other - two hundred and fifty.

Apparently, thanks to the art of the storyteller, all this fantasy story left her in no doubt. I could hardly wait for an evening walk with Korney Ivanovich to make him laugh with Marshak's invention.

How could it come to his mind? I laughed. - imagine, he works as a tiger, and you as a giraffe! He - three hundred, you - two hundred and fifty!

Korney Ivanovich, who at first laughed with me, suddenly said sadly:

Here, all my life like this: he is three hundred, I am two hundred and fifty ...

No matter how later Chukovsky and I asked Samuil Yakovlevich to repeat the story of how he was Marshak in a tiger skin, he refused, laughing:

I can't, it was an impromptu...

I did not often visit Marshak at home, but every time the meeting was enough for a long time. Not only writers, artists, editors visited Marshak. People of various professions succeeded each other in the chair, standing on the right at his desk. And he involved everyone in the circle of his big thoughts about poetry. Without fear of lofty words, I will say that there was a constant selfless service to poetry. Poems of Russian classics, Soviet poets and all those whom, according to Chukovsky, Marshak "turned into Soviet citizenship" by the power of his talent, - Shakespeare, Blake, Burns, Kipling ...

Here, the skill of Marshak himself was completely revealed to me - at first I naively believed that his poems for children were too simple in form, and even once said to the editor:

I can write such simple poems every day!

The editor chuckled.

I beg you, write them at least every other day.

It used to be that S. Ya. would read me a poem that had just been written on the phone, he would be childishly happy about one line, and demandingly ask about others: "What's better?" - and read countless options.

During the war in "Vechernyaya Moskva" there was a note about how carrier pigeons, taken away by the Nazis, returned to their homeland. The topic seemed close and interesting to children; I wrote the poem "Doves" and called Komsomolskaya Pravda.

Dictate, please, to the stenographer, - said the editor. - What are the poems about?

About homing pigeons, about them a curious note in "Evening Moscow".

About doves? - the editor was surprised. - Marshak has just dictated the verses "Doves" on the topic of this article.

The next morning, Marshak's poem appeared in Komsomolskaya Pravda. I decided to give my "Doves" to "Pionerskaya Pravda" and called S. Ya. to tell him that I also wrote poems about the same pigeons.

It will look strange - two poems with the same plot, - Marshak said displeasedly.

It’s different for me,” I said timidly.

But he was already getting angry. I did not want him to be angry with me again that I did not publish my poem. And, perhaps, Marshak was right ...

The transitions from kindness to severity were in the character of S. Ya. He himself knew this, which is probably why he liked the joke I wrote:

"Almost Burns"

A poet once to Marshak

Brought inaccurate string.

- Well, how is it? Marshak said.

He stopped being kind

He became an angry Marshak.

He even banged his fist:

- A shame! he said sternly...

When your line is bad

Poet, be afraid of Marshak,

If you are not afraid of God...

I look like, I don’t deny it, - Samuil Yakovlevich laughed.

I reread Marshak often. And poems, and inscriptions on the books presented to me. All of them are dear to me, but one in particular:

One hundred Shakespearean sonnets

And fifty four

I give Agnia Barto -

Lyre comrade.

Once upon a time, we really turned out to be lyre comrades. In "Native Speech" for the second grade, a poem was published for many years:

Let's remember the summer

Remember this summer

These days and evenings.

So many songs have been sung

On a warm evening by the fire.

We are on the forest lake

Went far away

Drank delicious steam

With light milk foam.

We weeded the gardens

Sunbathed by the river.

And in a large collective farm field

Collected spikelets.

M. Smirnov

This is how the poem was written. Here is his story: a group of children's writers, led by Marshak, took part in the compilation of "Native speech". It turned out that there were not enough poems about summer. I had a suitable poem, already published. Marshak suggested taking the first two stanzas from it and amending them. I had it written: "On the lawn, by the fire." He corrected "In a warm evening by the fire." Got better. I had lines: "We drank delicious fresh milk in the village." Marshak corrected: "With light foam" milk, which, of course, is also better. He wrote the third stanza himself.

How do we sign a poem? Two surnames under twelve lines - isn't it cumbersome? Samuil Yakovlevich asked.

Shall we sign M. Smirnov? I suggested.

For many poets, it is an urgent need to read a newly written poem to a person you believe. Sergei Mikhalkov, when he was still just Seryozha for everyone, somehow called me almost at one in the morning.

Something happened? I asked.

It happened: I wrote new poems, now I'll read it to you.

I have always especially appreciated those people into whose lives you can break into poetry at any moment. Such was Svetlov. He could be distracted from any business, from his own lines and listen to you with sincere interest, no matter what state of mind he himself was in. Here I am with trepidation reading him a new poem "There are such boys." Svetlov proposes to cut two lines, I immediately agree. Two others:

He frowns, he grunts,

Like drinking vinegar. -

Svetlov advises moving from the middle of the poem to the beginning.

Don't you understand, it will be a great start, he assures me.

But it seems to me that this will break the internal flow of the plot. Six months later, when I thought that Svetlov had forgotten about my poem, he asked me at a meeting:

Did you change those lines?

I shake my head.

All is not lost yet, you will still understand and rearrange in the one hundred and twenty-fifth edition.

Much has been written about Svetlov's inexhaustible wit. But sometimes in his wit there were far from joyful notes. A group of writers awarded orders and medals. Svetlov is not on the list. He says to me in the corridor of the Writers' Union:

Do you know what the other side of the coin is? Not allowed!

Sighing, he leaves.

I remembered that sigh of his when he was awarded the Lenin Prize. Posthumously...

We talked on the phone with Svetlov, almost as a rule, about work. More than once he spoke about his plan: to write ten fairy tales about how the ruble broke into dimes, each dime would have its own fairy tale. Later, he read me a passage about a penny girl, how all twenty of her nails on her hands and feet rejoiced when she lay down on the grass. And how some old man woke her up. "He was a little implausible, either from a legend, or from a nearby collective farm." What was said about him could refer to Svetov himself. He was also a little implausible, a little bit from the legend ...

We often talked about merry verses, about the value of a smile, and fell in unison on boring, dull lines. Svetlov wrote in his epigram:

I will establish the truth now

We do not like dull verses with you.

Oh Agnia! I love you so much,

That you can't write an epigram.

How happy I was to read this "unable to" ...

Fadeev also belonged to people who were ready to listen to poetry without fail. You could call him at the Writers' Union and, if you're lucky and he picks up the phone himself, ask: "Do you have a few minutes?"

New verses? - guessed Fadeev. - Read!

Alexander Alexandrovich himself was familiar with the impatient desire to read the pages he had just written to Vsevolod Ivanov, Vladimir Lugovsky, and many others.

When he was writing "The Young Guard", he called me, read the just finished excerpt from "Mother's Hand".

I think you'll like it, he said.

Liked "Mother's Hands" millions of people.

My literary "ambulance" was Lev Kassil. Long ago he said to me:

Why do you call your collections so uniformly: "Poems", "Your Poems", "Funny Poems", "Poems for Children"? If you could just give me a call, I'd come up with a more interesting name for you!

Since then, "for titles" to new poems, I called Kassil. He christened many of them, did it skillfully and with great pleasure. Sometimes, I agree to the name proposed by him, and he himself already rejects it, comes up with another one. Most often, he took out a line from my own poem in the title, and I was surprised - how did it not occur to me? Over time, I myself began to come up with names better, but each time I called Kassil for approval.

Of course, not only the attitude of fellow writers to my poems is important to me, not only their reaction. Sometimes I start reading new poems to everyone who comes or calls me. Not everyone knows how or wants to express their opinion and assessment, but whether a poem has reached it can be caught without words, even by the way a person breathes in a telephone receiver. When I read to another, I myself see the gaps in the poem more clearly. I am always interested in the opinions of young poets.

But about them a separate conversation.

Natalia Ursu

Literary quiz based on the works of K. I. Chukovsky, A. L. Barto, S. Ya. Marshak for preschool children

Program tasks:

1. Continue to deepen interest children to the work of children's writers K.I. Chukovsky, A. L. Barto, S. Ya. Marshak.

2. Encourage children recall titles and content works of writers with whom they have met before; experience the joy of meeting your favorite fairy-tale characters.

3. Form the ability to determine the name works according to the content of excerpts from them and according to illustrations.

4. Woo from children expressive reading works.

5. Systematize knowledge children about the work of your favorite writers.

preliminary work: Reading works A. L. Barto, K. I. Chukovsky, S. Ya. Marshak, conversations on them and looking at illustrations for them, memorizing poems, staging, dramatization, theatrical games by content works, word games "Say the opposite", "Know the Hero", "Who can you say that about?", "What, what, what?", "Good bad".

Material: books and illustrations for works, portraits of K.I. Chukovsky, A. L. Barto, S. Ya. Marshak; illustrations depicting objects according to the content of the poem by A. L. Barto"Toys" rewarding children for correct answers (origami daisies).

Quiz progress:

1. Brief conversation about the work of K.I. Chukovsky, A. L. Barto, S. Ya. Marshak and their biographies.

Target: continue to enrich the views children about the life and work of children's writers.

The teacher brings children for an exhibition of illustrations and books works by K. AND. Chukovsky, S. Ya. Marshak, A. L. Barto. The analysis of illustrations, the display of portraits of writers and familiarization children with their biography and work.

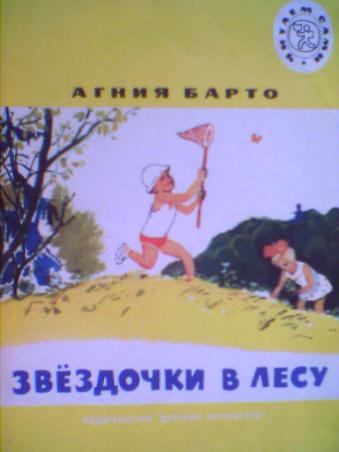

caregiver: guys, let's remember your favorite writers again and we'll start with Agnia Lvovna Barto. Her real name was Volova, she was born on February 17, 1906, in Moscow. She studied at the gymnasium, at the same time she studied at the choreographic school. In 1925, her first poems were published. During the years of the Great Patriotic War BUT. Barto was in evacuation in the city of Sverdlovsk. She went to the front with the reading of her poems, spoke on the radio, wrote for newspapers. For the collection "Poems for children" (in 1949) She was awarded a state prize. Poetry "Our Tanya is crying loudly" were dedicated to her daughter Tanya, and later, the image of the grandson Volodya is reflected in the cycle of poems "Vovka is a kind soul". Each of us in childhood had a book of poems by A. Barto, which we gladly read by heart, with almost no effort to remember them. Rhythm, rhymes, images and plots are close and understandable to every child. And, although they were written in the last century, more than one generation of our children will have an expression repeat: "I won't leave him anyway".

Our memory of a woman-poet who devoted her whole life and work to children is also long-lived.

And now let's talk about grandfather Korney himself - a writer, poet and translator. The real name of the writer is Nikolai Vasilievich Korneichukov. He has always been a cheerful and cheerful person. He was born on March 31, 1882 in St. Petersburg. He was 3 years old when he left to live only with his mother. He spent his childhood in Odessa and Nikolaev. He was expelled from the Odessa gymnasium due to "low" origin because her mother worked as a laundress. The family lived very hard on the mother's small salary, but the young man did not give up, he read a lot, studied on his own and passed the exams, receiving a matriculation certificate.

From an early age K. Chukovsky started to wonder poetry: wrote poems and even poems.

Do you remember how Chukovsky became a children's poet and storyteller? - By chance. And it turned out like this. His little son got sick. Korney Ivanovich was taking him home on the night train, the boy was capricious, moaning, crying. In order to somehow entertain him, his father began to tell him a fairy tale “Once upon a time there was a crocodile, he walked the streets ...” the son calmed down and began to listen to his father. A few days later he asked his father to repeat the tale he had told. It turned out that the son memorized it all word for word. After that case Chukovsky began to write children's stories.

Korney Ivanovich has not been among us for a long time, but his books live and will live for a long time to come. From an early age, his poems bring joy to everyone, not only you, but also your parents, grandparents cannot imagine their childhood without "Aibolita", "Cockroach", "Fedorina grief", "Flies-Tsokotuhi", "Phone".

And also, guys, we have no less beloved by you children's writer S. Ya. Marshak(poet, playwright, translator, literary critic) . He was born in 1887 in the family of a factory technician, a talented inventor, in Voronezh. His father supported in children the desire for knowledge, interest in the world, in people. Studied Marshak in the gymnasium, in the city of Ostrogozhsk near Voronezh. The teacher of literature instilled in him a love for classical poetry and encouraged the first literary experiences of the future poet. Marshak created a children's theater in the city of Krasnodar, in which his work as a children's writer began.

In 1923 in Petrograd he wrote his first original fairy tales in verse. "The Tale of the Stupid Mouse", "Fire", "Mail". His play-tales are especially popular. "Twelve months", "Smart Things", "Cat house" that you are well aware of.

2. Speech game "Tell a Poem"

Target: develop the intonation side of speech, memory; activate speech activity children.

caregiver: Guys, do you remember your first poems about A. Barto?

Children: remember.

caregiver: and let's play such a game, I will lay out cards with the image of toys, and you, if you wish you will come up and tell poems about the toy that is shown on the card you have chosen. (Children come up, choose a card, recite a poem, and the teacher makes sure that they speak with expression and give out incentive prizes).

caregiver: well done, guys, even though you learned these poems for a very long time, you can immediately see that you remember them very well.

And now let's move on to the fairy tales of K.I. Chukovsky. What are their names?

Children: "Cockroach", "Moydodyr", "Fly Tsokotukha".

3. Game "Name the story"

Target: consolidate knowledge children of works K. AND. Chukovsky, let down children

caregiver: Guys, you remember the names of fairy tales well, and now let's try to guess them from the passages I read out. (The teacher reads out excerpts from the fairy tales of K.I. Chukovsky and children guess)

1) Oh, you are my poor orphans,

Irons and frying pans are mine.

Come back, you are unwashed home. (Fedorino grief)

2) Who is told to tweet,

Don't purr!

Who is commanded to purr -

Don't tweet!

Do not be a crow cow

Do not fly frogs under the cloud! (Confusion)

3) And such rubbish

All day:

Ding-dee laziness, ding-dee laziness!

Either a seal will call, or a deer! (Telephone)

4) And growls and screams,

And wiggles his mustache:

"Wait, don't rush

I'll swallow you up in no time!

I’ll swallow, I’ll swallow, I won’t pardon.” (Cockroach)

5) Dear guests, help!

Kill the villain spider!

And I fed you, and I watered you

Don't leave me in my last hour... (Fly Tsokotukha)

6) Darkness has come

Don't go through the gate...

Who got on the street -

Got lost and lost. (stolen sun).

7) And the hare came running,

And screamed: Hey, hey!

My bunny got hit by a tram!

My bunny, my boy

Got hit by a tram! (Aibolit).

8) Little children! No way,

Do not go to Africa, walk to Africa!

Sharks in Africa, Gorillas in Africa

Big angry crocodiles in Africa

They will bite, beat and offend you ... (Barmaley)

9) Let's wash and splash,

Swim, dive, tumble,

In a tub, trough, tub,

In the river, stream, in the ocean,

And in the bath, and in the bath, always and everywhere - the eternal glory of water! (Moidodyr)

caregiver: well done, guys, and the words from the last fairy tale should be the motto for everyone and always! We must never forget about cleanliness and hygiene! If we listen to the advice of Moidodyr and be friends with water, we will never get sick!

4. Fairy tale quiz K. AND. Chukovsky.

Target: consolidate knowledge children of works K. AND. Chukovsky, let down children to the understanding of the artistic images of the writer.

caregiver: and now I want to offer you questions about the fairy tales of K.I. Chukovsky. You guys be careful. Try to answer clearly and quickly.

Questions Quizzes.

1) What did the bunnies ride in a fairy tale "Cockroach"? (by tram)

2) What fell on the elephant in a fairy tale "Cockroach"? (moon)

3) Why did the stomachs of herons hurt, who asked to send them drops in a poem "Telephone"? (they ate frogs)

4) What did Dr. Aibolit regale sick animals in Africa? (Gogol-mogol)

5) Why a pig from a poem "Telephone" asked to send a nightingale to her? (to sing along with him)

6) Who attacked Mukha-Tsokotukha? (spider)

7) What did the brave mosquito who saved Mukha-Tsokotukha carry? (flashlight and saber).

8) Where did Aibolit go by telegram? (to Africa)

9) Aibolit's profession? (doctor)

10) The mustachioed character of the fairy tale by K.I. Chukovsky? (Cockroach).

11) What fairy tale begins with a name day and ends with a wedding? (Fly Tsokotukha)

12) What a formidable name said Moidodyr, after hitting a copper basin? (Karabaras)

5. Game-pantomime "Picture a Character" according to the content of the poem S. Ya. Marshak"Children in a Cage"

Goals: keep learning children characterize literary characters; develop figurative and plastic creativity children.

The teacher reads out a poem, and the children depict with facial expressions and posture the characteristic features of each animal giant giraffe, reaching for branches of a tall tree, an elephant waving its trunk, and its heavy gait; convey by movement, facial expressions and posture the behavior of a tiger cub, an owl, a camel according to the text of the poem.

tiger cub

Hey don't get too close

I'm a tiger cub, not a pussycat!

Swan

Why does water flow

From this baby?

He recently from the pond,

Give me towels!

Poor little camel:

The child is not allowed to eat.

He ate this morning

Only two such buckets!

They gave shoes to an elephant.

He took one shoe

And said: - Need wider,

And not two, but all four!

Look at the little owls -

The little ones sit side by side.

When they don't sleep

They're eating.

When they eat

They don't sleep.

Picking flowers is easy and simple

Children of small stature

But to one who is so high

It's not easy to pick a flower!

The teacher praises children, distributes incentive prizes.

Outcome: in the end quiz, the teacher fails again children to the table with books by children's writers and draws attention to those of them that were not the subject quiz, offers to read them at home with parents, older sisters or brothers and draw the episodes they like most from the read works.

List literature:

1. Reader for children 3-5 years old(to the program "Development") N. F. Astaskova, O. M., Dyachenko. Moscow. New school. 1996, -239 p.

2. Ushakova O. S., Gavrish N. V. Acquaintance preschoolers with literature: Summaries of classes. - M.: TC Sphere, 2002. - 224 p. (Series "Development Programs").

3. Mukhaneva M. D. Theatrical classes in the children's garden: Benefit for workers preschool institutions. - M .: TC "Sphere", 2001. - 128 p.

4. Falkovich T. A., Barylkina L. P. Development of speech, preparation for mastering letters: Classes for preschoolers in institutions of additional education. - M.: VAKO, 2005. - 228 p. (preschoolers: teach, develop, educate).

The personality of Agnia Lvovna herself, as far as the very few biographical information (and, to no lesser extent, some biographical omissions) allow us to judge this, decisively influenced the theme and nature of her poetic works. The daughter of a prominent Moscow veterinarian began writing poetry at an early age. In all likelihood, little Agnia's lack of parental attention, in general, and paternal attention, in particular, determined the main motives of her work. Perhaps the professional practice of the father, which distracted considerable time from communication with her daughter, served as a source of special poetic images for her. Various animals, which, as objects of paternal love and care, seemed to replace their own child, probably became, in the perception of little Agnia, a kind of phantoms of herself and forever remained associated with the theme of displacement, abandonment and loneliness.

One can only guess how consciously or unconsciously the veterinarian's daughter experienced a lack of parental warmth at the age of five or six, but in her thirties she framed these experiences in poetic texts of such psychological accuracy, metaphorical depth and universality that they became, in essence, a kind of verbal projects. . Having taken shape in literary texts, the theme of loneliness and repression has acquired the quality of compactly folded plot information, which is updated and unfolds in situations of psychological resonance between a first-order medium (author) and a second-order medium (reader).

In the life of Agnia Lvovna herself, the role of her own text as a fateful project manifested itself with particular force. When, as a young poet, she was introduced to the people's commissar of culture A.V. Lunacharsky as a young poet, he asked her to read him some poem of his composition. The girl surprised the people's commissar a lot beyond her age with a minor poem called "Funeral March". Then the perplexed people's commissar recommended young Agnia to compose something more life-affirming and positive. However, over the years, Barto's poetic texts have by no means become less dramatic. Even outwardly positive poems retain her inner tragedy. And some of them are pierced by the chill of death.

The theme of the lost, abandoned, displaced child, which runs through all the work of Agnia Barto, has programmed a lot in own life poetesses. Shortly after the war, Agniya Barto lost her son. It was a ridiculous, tragic loss resulting from an accident. If I'm not mistaken, the boy died riding a bicycle.

♦ Agnia Lvovna Barto (1906-1981) was born on February 17 in Moscow in the family of a veterinarian. She received a good home education, which was led by her father. She studied at the gymnasium, where she began to write poetry. At the same time she studied at the choreographic school.

♦ The first time Agniya got married early: at the age of 18. young handsome poet Pavel Barto, who had English and German ancestors, immediately liked the talented girl Agnia Volova. They both idolized poetry and wrote poetry. That's why mutual language young people found it right away, but ... Nothing but poetic research connected their souls. Yes, they had a common son, Igor, whom everyone at home called Garik. But it was with each other that the young parents suddenly became incredibly sad.  And they parted ways. Agnia herself grew up in a strong, friendly family, so divorce was not easy for her. She was worried, but soon devoted herself entirely to creativity, deciding that she should be true to her calling.

And they parted ways. Agnia herself grew up in a strong, friendly family, so divorce was not easy for her. She was worried, but soon devoted herself entirely to creativity, deciding that she should be true to her calling.

♦ Agnia's father, Moscow veterinarian Lev Volov wanted his daughter to become a famous ballerina. Canaries sang in their house, Krylov's fables were read aloud. He was known as a connoisseur of art, loved to go to the theater, especially loved ballet. That is why young Agnia went to study at the ballet school, not daring to resist the will of her father. However, in between classes, she enthusiastically read the poems of Vladimir Mayakovsky and Anna Akhmatova, and then wrote down her creations and thoughts in a notebook. Agnia, according to her friends, at that time was outwardly similar to Akhmatova: tall, with a bob haircut ... Under the influence of the work of her idols, she began to compose more and more often.

♦ At first, these were poetic epigrams and sketches. Then came the poetry. Once, at a dance performance, Agnia, to the music of Chopin, read her first poem "Funeral March" from the stage. At that moment, Alexander Lunacharsky entered the hall. He immediately saw the talent of Agnia Volova and offered to engage in literary work professionally. Later, he recalled that, despite the serious meaning of the poem, which he heard performed by Agnia, he immediately felt that she would write funny poems in the future.

♦ When Agnia was 15 years old, she got a job at the clothing store - she was too hungry. The salary of the father was not enough to feed the whole family. Since they were hired only from the age of 16, she had to lie that she was already 16. Therefore, until now, Barto's anniversaries (in 2007 it was 100 years since the birth) are celebrated two years in a row. ♦ She always had a lot of determination: she saw the goal - and forward, without swaying and retreating. This feature of her showed through everywhere, in every little thing. Once in a torn civil war Spain, where Barto went to the International Congress for the Defense of Culture in 1937, where she saw with her own eyes what fascism was (congress meetings were held in a besieged burning Madrid), and just before the bombing she went to buy castanets. The sky howls, the walls of the store bounce, and the writer makes a purchase! But after all, the castanets are real, Spanish - for Agnia, who danced beautifully, it was an important souvenir. Alexey Tolstoy then, with malice, he was interested in Barto: did she buy a fan in that shop in order to fan herself during the next raids? ..

♦ In 1925 Agnia Barto's first poems "Chinese Wang Li" and "Bear Thief" were published. They were followed by "The First of May", "Brothers", after the publication of which the famous children's writer Korney Chukovsky said that Agniya Barto is a great talent. Some poems were written jointly with her husband. By the way, despite his reluctance, she kept his last name, with which she lived until the end of her days. And it was with her that she became famous all over the world.

♦ The first huge popularity came to Barto after he saw the light of a cycle of poetic miniatures for the smallest "Toys" (about a bull, a horse, etc.) - in 1936 Agnia's books began to be published in gigantic editions ...

♦ Fate did not want to leave Agnia alone and one fine day brought her to Andrey Shcheglyaev.  This talented young scientist purposefully and patiently courted a pretty poetess. At first glance, these were two completely different people: a "lyricist" and a "physicist". Creative, sublime Agniya and heat power engineer Andrey. But in reality, an extremely harmonious union of two loving hearts has been created. According to family members and close friends of Barto, for almost 50 years that Agnia and Andrei lived together, they never quarreled. Both worked actively, Barto often went on business trips. They supported each other in everything. And both became famous, each in their own field. Agnia's husband became famous in the field of thermal power engineering, becoming a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences.

This talented young scientist purposefully and patiently courted a pretty poetess. At first glance, these were two completely different people: a "lyricist" and a "physicist". Creative, sublime Agniya and heat power engineer Andrey. But in reality, an extremely harmonious union of two loving hearts has been created. According to family members and close friends of Barto, for almost 50 years that Agnia and Andrei lived together, they never quarreled. Both worked actively, Barto often went on business trips. They supported each other in everything. And both became famous, each in their own field. Agnia's husband became famous in the field of thermal power engineering, becoming a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences.

♦ Barto and Shcheglyaev had a daughter, Tanya, about whom there was a legend that it was she who was the prototype of the famous rhyme: “Our Tanya is crying loudly.” But this is not so: poetry appeared earlier. Even when the children grew up, it was decided to always live as a big family under the same roof, together with the wives-husbands of the children and grandchildren - Agnia wanted so much.

♦ Barto and Shcheglyaev had a daughter, Tanya, about whom there was a legend that it was she who was the prototype of the famous rhyme: “Our Tanya is crying loudly.” But this is not so: poetry appeared earlier. Even when the children grew up, it was decided to always live as a big family under the same roof, together with the wives-husbands of the children and grandchildren - Agnia wanted so much.

♦ In the late thirties, she traveled to this "neat, clean, almost toy country", heard Nazi slogans, saw pretty blond girls in dresses "decorated" with a swastika. She realized that war with Germany was inevitable. To her, sincerely believing in the universal brotherhood, if not adults, then at least children, all this was wild and scary. But the war had not been too hard on her. She was not separated from her husband even during the evacuation: Shcheglyaev, who by that time had become a prominent power engineer, was sent to the Urals. Agnia Lvovna had friends in those parts who invited her to live with them. So the family settled in Sverdlovsk. The Urals seemed distrustful, closed and harsh people. Barto had a chance to meet Pavel Bazhov, who fully confirmed her first impression of the locals. During the war, Sverdlovsk teenagers worked at defense factories instead of adults who had gone to the front. They were wary of the evacuees. But Agnia Barto needed to communicate with children - she drew inspiration and plots from them. In order to be able to communicate with them more, Barto, on the advice of Bazhov, received the profession of a turner of the second category. Standing at the lathe, she argued that "also a man." In 1942, Barto made one last attempt to become an "adult writer". Or rather, a front-line correspondent. Nothing came of this attempt, and Barto returned to Sverdlovsk. She understood that the whole country lives according to the laws of war, but still she missed Moscow very much.

♦ Barto returned to the capital in 1944, and almost immediately life went back to normal. In the apartment opposite the Tretyakov Gallery, the housekeeper Domash was again engaged in housekeeping. Friends were returning from evacuation, son Garik and daughter Tatyana again began to study. Everyone was looking forward to the end of the war. On May 4, 1945, Garik returned home earlier than usual. Home was late with dinner, the day was sunny, and the boy decided to ride a bicycle. Agnia Lvovna did not object. It seemed that nothing bad could happen to a fifteen-year-old teenager in the quiet Lavrushinsky Lane. But Garik's bicycle collided with a truck that had come around the corner. The boy fell to the pavement, hitting his temple on the sidewalk curb. Death came instantly.  With son Igor

With son Igor

♦ We must pay tribute to Agnia Lvovna's strength of spirit - she did not break. Moreover, her salvation was the cause to which she devoted her life. After all, Barto also wrote scripts for films. For example, with her participation, such well-known tapes as "Foundling" with Faina Ranevskaya, "Alyosha Ptitsyn develops character" were created. She was also active during the war: she went to the front with the reading of her poems, spoke on the radio, and wrote for newspapers. And after the war, and after the personal drama, she did not cease to be at the center of the country's life.  Frame from the film "Foundling"

Frame from the film "Foundling"

"

Alyosha Ptitsyn develops character" (1953)

"

Alyosha Ptitsyn develops character" (1953)

♦ Later, she was the author of a large-scale campaign to search for relatives who were lost during the war. Agniya Barto began to host a program on the radio Find a Person, where she read out letters in which people shared fragmentary memories that were not enough for an official search, but viable for word of mouth. For example, someone wrote that when he was taken away from home as a child, he remembered the color of the gate and the first letter of the street name. Or one girl remembered that she lived with her parents near the forest and her dad's name was Grisha ... And there were people who restored the overall picture. For several years of work on the radio, Barto was able to unite about a thousand families. When the program was closed, Agniya Lvovna wrote the story "Find a Man", which was published in 1968.

♦ Agniya Barto, before submitting the manuscript for printing, wrote an infinite number of options. Be sure to read poems aloud to household members or by phone to fellow friends - Kassil, Svetlov, Fadeev, Chukovsky. She listened carefully to criticism, and if she accepted, she redid it. Although once she categorically refused: the meeting, which decided the fate of her "Toys" in the early 30s, decided that the rhymes in them - in particular in the famous "They dropped the bear on the floor ..." - were too difficult for children.

Tatyana Shcheglyaeva (daughter)

Tatyana Shcheglyaeva (daughter)

“She did not change anything, and because of this, the book came out later than it could have,” remembers daughter Tatyana - Mom was generally a person of principle and often categorical. But she had a right to it: she did not write about what she did not know, and she was sure that children should be studied. I have been doing this all my life: I read letters sent to Pionerskaya Pravda, went to nurseries and kindergartens - sometimes for this I had to introduce myself as an employee of the public education department - listened to what the children were talking about, just walking down the street. In this sense, my mother always worked. Surrounded by kids (still young)

♦ House Barto was the head. The last word was always hers. The household took care of her, did not demand to cook cabbage soup and bake pies. This was done by Domna Ivanovna. After the death of Garik, Agnia Lvovna began to fear for all her relatives. She needed to know where everyone was, that everyone was all right. “Mom was the main helmsman in the house, everything was done with her knowledge,” recalls Barto's daughter, Tatyana Andreevna. - On the other hand, they took care of her and tried to create working conditions - she did not bake pies, she did not stand in lines, but, of course, she was the mistress of the house. Nanny Domna Ivanovna lived with us all her life, who came to the house back in 1925, when my elder brother Garik was born. This was a very dear person for us - and the hostess is already in a different, executive sense. Mom always took care of her. She could, for example, ask: “Well, how am I dressed?” And the nanny said: “Yes, it’s possible” or: “Strangely gathered”

♦ Agnia has always been interested in raising children. She said: “Children need the whole gamut of feelings that give birth to humanity” . She went to orphanages, schools, talked a lot with the kids. Driving around different countries, came to the conclusion that a child of any nationality has a rich inner world. For many years, Barto headed the Association of Literature and Art for Children, was a member of the international Andersen jury. Barto's poems have been translated into many languages of the world.

♦ She passed away on April 1, 1981. After the autopsy, the doctors were shocked: the vessels were so weak that it was not clear how the blood had flowed into the heart for the past ten years. Once Agniya Barto said: "Almost every person has moments in his life when he does more than he can." In her case, it was not a minute - she lived like that all her life.

♦ Barto loved to play tennis and could arrange a trip to capitalist Paris to buy a pack of drawing paper she liked. But at the same time, she never had a secretary, or even a study - only an apartment in Lavrushinsky Lane and an attic in a dacha in Novo-Daryino, where there was an old card table and stacks of books piled up.

♦ She was non-confrontational, adored practical jokes and did not tolerate swagger and snobbery. Once she arranged a dinner, set the table - and attached a sign to each dish: "Black caviar - for academicians", "Red caviar - for corresponding members", "Crabs and sprats - for doctors of sciences", "Cheese and ham - for candidates "," Vinaigrette - for laboratory assistants and students. They say that this joke sincerely amused the laboratory assistants and students, but the academicians lacked a sense of humor - some of them were then seriously offended by Agnia Lvovna.

♦ Seventies. In the Writers' Union meeting with Soviet cosmonauts. On a piece of paper from a notebook, Yuri Gagarin writes: "They dropped the bear on the floor ..." and hands it to the author, Agniya Barto. When Gagarin was subsequently asked why these particular verses, he replied: "This is the first book about kindness in my life."

Updated on 08/12/14 14:07:

Oops ... I forgot to insert a piece from myself at the beginning of the post)) Probably, it was the poems of Agnia Barto that influenced the fact that since childhood I feel sorry for dogs, cats, grandparents who beg for alms (I'm not talking about those who are like watch every day stand in the same subway crossings ...). I remember, as a child, I watched the cartoon "Cat's House" and literally sobbed - I felt so sorry for the Cat and the Cat, because their house burned down, but they were pitied by the kittens, who themselves have nothing))))) (I know it's Marshak). But the poor child (I) was crying from my pure, naive, childish kindness! And I learned kindness not only from mom and dad, but also from such books and poems that Barto wrote. So Gagarin very accurately said ...

Updated on 08/12/14 15:24:

Persecution of Chukovsky in the 30s

Such a fact was. Chukovsky's children's poems were subjected to Stalin era cruel harassment, although it is known that Stalin himself repeatedly quoted The Cockroach. The persecution was initiated by N. K. Krupskaya, inadequate criticism came from both Agnia Barto and Sergei Mikhalkov. Among the party critics of the editors, even the term "Chukovshchina" arose. Chukovsky undertook to write an orthodox-Soviet work for children, The Merry Collective Farm, but did not do so. Although other sources say that she did not quite poison Chukovsky, but simply did not refuse to sign some kind of collective paper. On the one hand, not in a comradely way, but on the other ... Decide for yourself) In addition, in last years Barto visited Chukovsky in Peredelkino, they maintained a correspondence ... So either Chukovsky is so kind, or Barto asked for forgiveness, or we don’t know much.

In addition, Barto was also seen in the persecution of Marshak. I quote: " Barto came to the editorial office and saw proofs of Marshak's new poems on the table. And he says: "Yes, I can write such poems at least every day!" To which the editor replied: "I beg you, write them at least every other day ..."

Updated on 09/12/14 09:44:

I continue to reveal the topic of bullying)) As for Marshak and others.

At the end of 1929 - beginning of 1930. on the pages of "Literaturnaya Gazeta" a discussion "For a truly Soviet children's book" unfolded, which set three tasks: 1) to reveal all kinds of hack work in the field of children's literature; 2) to promote the formation of principles for the creation of truly Soviet children's literature; 3) to unite qualified cadres of real children's writers.

From the very first articles that opened this discussion, it became clear that she had taken a dangerous path, the path of persecution of the best children's writers. The works of Chukovsky and Marshak were summed up under the heading of "defective literature" and simply hack-work. Some participants in the discussion "discovered" the "alien orientation of Marshak's literary talent" and concluded that he was "obviously alien to us in ideology" and his books were "harmful and empty." Starting in the newspaper, the discussion soon spread to some magazines. The discussion exaggerated the mistakes of talented authors and propagated the non-fiction works of some writers.

The nature of the attacks, the tone in which these attacks were expressed, were absolutely unacceptable, as a group of Leningrad writers stated in their letter: "attacks on Marshak are in the nature of harassment."

Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky is a children's poet with a capital letter, a real popular favorite. Without the poems of Korney Chukovsky, it is impossible to imagine either the world of children's poetry, or the children's world itself - kind and colorful. It is his poetic tales that form in the children's mind a positive attitude towards the environment. Most of the works for children were written by Korney Chukovsky about a century ago, but still remain one of the most beloved by children. Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky is the most published author of children's literature in Russia.

ROOT CHUKOVSKY FAIRY TALES FOR CHILDREN

CHILDREN'S WRITER ROOT IVANOVICH CHUKOVSKY

Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky is a pseudonym.

The real name of this writer, children's poet, translator, literary critic and literary critic is Nikolai Vasilyevich Korneychukov.

Chukovsky wrote about himself as follows:

“I was born in St. Petersburg in 1882, after which my father, a St. Petersburg student, left my mother, a peasant woman in the Poltava province; and she and her two children moved to live in Odessa. Probably, at first, her father gave her some money to raise children: I was sent to the Odessa gymnasium, from the fifth grade of which I was unfairly expelled.

Having tried many professions, from 1901 I began to publish in Odessa News, writing mainly articles about exhibitions of paintings and about books. Sometimes - very rarely - poetry.

In 1903 the newspaper sent me as a correspondent to London. I turned out to be a very bad correspondent: instead of attending parliamentary meetings and listening to speeches about high politics there, I spent whole days in the library of the British Museum ... ( English language I learned by myself.)".

Upon returning from London to St. Petersburg, Korney Ivanovich seriously took up literary criticism. He devoted almost all his time to this profession, loved it very much and considered it his only profession.

Chukovsky initially did not even think about writing works for children. He continued to criticize children's poets in his articles, focusing on the dullness of their creations, completely devoid of rhyme and rhythm. On this occasion, Maxim Gorky, having met Chukovsky by chance on a train, suggested that instead of harsh criticism, Korney Ivanovich himself try to write a good poetic tale as an example.

After this conversation, Chukovsky sat down at his desk many times, but each time he came to the conclusion that he had no talent for writing children's fairy tales.

And yet the fairy tales were written by Chukovsky. But they were not written intentionally, by accident.

As the author himself mentions: “It so happened that my little son fell ill, and it was necessary to tell him a fairy tale. He fell ill in the city of Helsinki, I took him home on the train, he was naughty, cried, moaned. In order to somehow calm his pain, I began to tell him to the rhythmic roar of the train:

lived and was

Crocodile.

He walked the streets...

The verses spoke for themselves. I didn't care at all about their shape. And in general, I didn’t think for a minute that they had anything to do with art. My only concern was to divert the attention of the child from the attacks of the disease that tormented him. Therefore, I was in a terrible hurry: there was no time to think, pick up epithets, look for rhymes, it was impossible to stop even for a moment. The whole bet was on speed, on the fastest alternation of events and images, so that the sick little boy did not have time to moan or cry. So I chattered like a shaman:

And give him a reward

One hundred pounds of grapes

One hundred pounds of chocolate

One hundred pounds of marmalade

And a thousand pounds of ice cream.